PANCHA KOŚA – THE FIVE BODIES

The human body is our vehicle to express ourselves in the world. But little do we know what the human body is. Yogis have studied the body for thousands of years and have developed a basic philosophy around it. The principal composition of the human body is of five ‘vessels’ or koshas:

- annamaya kosha: the food vessel

- pranamaya kosha: the vital energy vessel

- manomaya kosha: the mental vessel

- vidjnanamaya kosha: the intellectual vessel

- anandamaya kosha: the bliss vessel

Our KARMAS (actions) and SAMSKĀRAS (memories and experiences) are stored in the Koshas. They form the partitions between the individual soul and the universal Self. Liberation – MOKSHA – therefore means to release the Ātmā from the limitations of the Koshas. In order to become one with something we must develop the same qualities as that with which we wish to unite. Until we have released ourselves from the Koshas, while we still hang onto our personal ego and continue to identify with the little “i”, we cannot become one with the Infinite.

See below the picture of all 5 koshas

FUEL FOR IDENTITY: LIKES & DISKLIKES

When we identify ourselves as the body-mind, we are naturally driven to pursue what we like or what we think is good and avoid what we dislike or what we think is bad. We live our lives seeking pleasure and fulfillment in material and mental ob- jects. Material objects are those that we can buy with money, whereas mental ob- jects are those that we seek to feel complete: fame, notoriety, success, love, rela- tionships, athletic achievements, and so on. Powered by certain brain and hor- monal pathways, this endless seeking pervades all spheres of life, and we attribute our happiness or unhappiness to what we get or don’t get.

We try to hold on to the good things, but they never last—the newer car model becomes more attractive than the one we have, fame comes and goes, spouses die, and children grow up. Even if the good things do last, they don’t seem to give us the same extent of joy that they initially did. After thirty years in the same job, we feel uninspired and long for more. After a while, the big house we saved up for feels burdensome with all the maintenance. We go on diets, pursue extensive exer- cise programs, and invest in anti-aging products, finding that the body ages de- spite our best efforts.

When we don’t have the things we want, we crave them. When we get what we want, we fear losing them. Our default “pull and push” mode of operation deter- mines the way we relate to ourselves and others. Constant evaluation, judgment, and comparison form the basis of relationships—we like some people and dislike others. This attitude would be fine if we always get what we want and never what we don’t want, but because life doesn’t work that way, we have a constant under- lying sense of being powerless. Our likes and dislikes become the labels that form our identity; they become who we are.

Having an incurable ailment like heart disease in this situation is devastating. Since we don’t like having chronic diseases, our dislike of disease becomes our source of suffering. We want to do away with the disease because it threatens our identity. Prevention and treatment in this default model are thus based on the as- sumption that having what we want determines our happiness or suffering. Dis- ease becomes the enemy that needs to be destroyed, as we see with the wide- spread “fights against” cancer, heart, or Alzheimer’s disease.

(Dr. Kavitha Chinnaiyan)

THE BRAIN

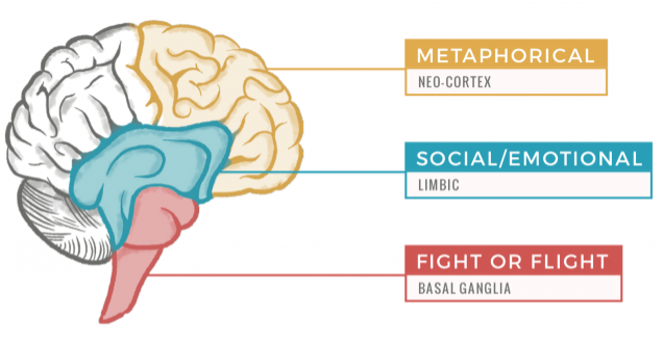

Consisting of nearly 100 billion neurons, our brains were built from the “bottom up,” since nature prefers to add on to what it has already produced rather than re- create its efforts.

Reptilian Brain

Right above where your spinal cord meets your brain is the most primitive part, known as the reptilian brain. Together with the hypothalamus that sits right above it, the reptilian brain is responsible for basic functions of your body, such as breathing, heartbeat, sleep, and excretion. Your reptilian brain also regulates your immune and hormonal functions (much will be said about this in coming chap- ters), acting as the switch between your emotions and your body. You can see your reptilian brain in action if you have anxiety-related diarrhea or constipation or if you develop hyperventilation with stress or have trouble sleeping because you’re wor- rying too much about your upcoming work meeting.

Mammalian Brain

Located directly above the reptilian brain is your limbic system, known as the mammalian brain. Known as the seat of emotions, the limbic system has devel- oped in response to experience. It is called mammalian because reptiles don’t have this ability to the extent that mammals do. Take a lizard, for instance. Its life is dic- tated by a drive to remain safe from predators, maintain its body temperature (since it is cold-blooded), and reproduce. Its brain doesn’t have a great capacity to learn from experience; it runs on instinct. It doesn’t have the ability to change its behavior based on past experience to the same extent as mammals.

Mammals

(including us humans), on the other hand, can learn from previous stimuli that caused a specific response and change course accordingly, thanks to the limbic system. The mammalian brain is thought to have been added on to the reptilian brain to make social order possible. It enables the formation of herds and groups, social dominance, the need for contact with other members of the herd, compe- tition for food and mates, and parental attachment—all the characteristics that we have in common with other mammals. The limbic system is what makes us learn to respond to stimuli in certain ways. We can thank the limbic system for all our conditioned responses (including Pavlov’s dogs that salivated at the mere sound of a bell and Ader’s mice that be- came nauseated with sweetened water, as we saw above). Your limbic system locks you in to particular responses to stimuli based on your past experience. This is why we can turn to ice cream for comfort or dislike someone instantly. You may have no conscious memory of the first time you created a response, which is usually in early childhood. When you have an aversion or attraction to someone or some- thing, certain neurohormonal pathways are being lit up that link them to the past unpleasant or pleasant experience. Particular hormones are released in response to stimuli that act as an alarm system, telling us if it is good or bad.

These pathways ensure our social and cultural conditioning—this is how we learn to behave in ways that enable our survival and reproduction, the two most critical functions as far as our brains are concerned. These pathways make us constantly scan our inter- nal and external environments to seek out the ones that feel good and avoid the ones that feel bad.

Human Brain

The top layer of your brain is the neocortex or what is called the human brain, which is much more developed than that of other mammals. Your neocortex is what makes you human, allowing you to dream big, solve math problems, predict what might happen tomorrow, sort out your finances, use words to convey what you are thinking, plan for the future, and control your actions. The surface of the neocortex consists of deep grooves and folds and is divided into the left and right brains, connected by a thick bundle of nerve fibers known as the corpus callosum.

Each half of your brain controls the movements of the opposite side of your body. In general, your left brain is more adept at logic, language, and reasoning, while your right facilitates music, expressing emotions, intuition, and creativity. However, both halves of your brain work together and with the limbic system to process the information coming in from the world around you and how you re- spond to it. Your neocortex takes in the information, but your limbic system is the one that determines if it is good or bad.

Your neocortex cannot produce the hormones that make you feel pain and pleasure; only your limbic system can. Your limbic system, on the other hand, needs your neocortex to give meaning to your experience of pleasure and pain. Without the neocortex, you cannot find meaning in your daily experiences, a quality that we humans thrive on. The neocortex was added on to the mammalian brain to recognize patterns be- tween the past, present, and future. It is the part that not only enables learning from past experience but also imagining how that might affect the future. This is where you learn to anticipate feeling good with ice cream or bad with certain “types” of people. This extraordinary ability of finding meaning in experience by linking to the past and anticipating the future is responsible for driving the evolu- tion of technology, medicine, space travel, and world events.

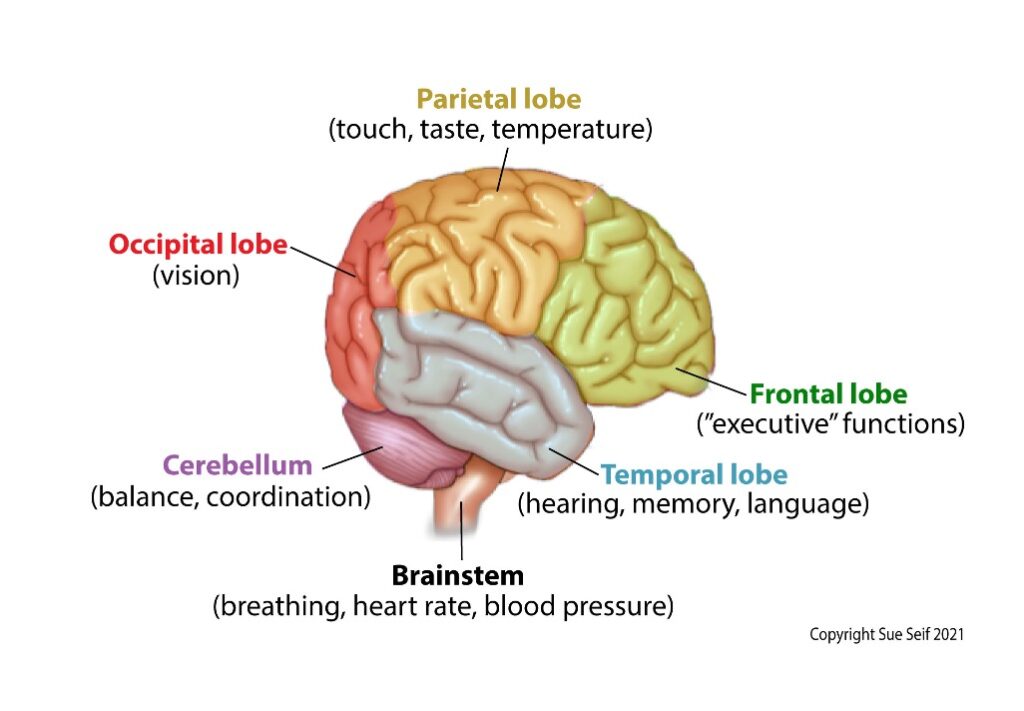

Lobes of the Brain

Let’s take a tour of the vast neocortex that controls the various functions of being a higher mammal. Your very large frontal lobe enables your ability to think of abstract concepts, control your movement, and use words to express yourself. In fact, your prefrontal cortex (the front part of the frontal lobe) is responsible for what we call “executive functions.” This is the part of the brain that determines your personality, makes you differentiate between what to do and what not to do, allows you to fashion your actions and thoughts based on your internal goals, sup- press them when they are inappropriate according to your social and cultural conditioning, predict what to expect, and learn from your past. The frontal lobe controls short-term memory, while long-term memory is coordinated by the temporal lobe.

Along with the hippocampus (remember that is the part of your brain where neurons can regenerate based on learning), the temporal lobe creates long-term memories, including visual ones. This is the part of your brain you can thank for memories from your childhood, travels, and experiences that help you remember faces, places, and things as if they happened yesterday. The temporal lobe makes it possible for us to recognize objects, and, along with the parietal lobe, to process sounds into meaningful language.

Your parietal lobe takes in the information from your various senses to inte- grate it into a coherent whole. It determines your sense of space and how you move through it, what the different stimuli such as touch, pain, and temperature on your skin mean, and what words and language refer to. It is also the part of the brain that allows you to see things in your “mind’s eye,” while your occipital lobe is associated with processing sight.

All the lobes work together to take in information from our environment and re- spond to it. What we see, hear, smell, taste, and touch is processed in the tem- poral, parietal, and occipital lobes. Memories are created via the temporal lobe, and through the executive functions of the frontal lobe that refers to those memo- ries, we respond and act according to our social and cultural contexts. Of course, this is an oversimplification of a very complex process that is still being unraveled, but you get the point—your neocortex is what makes you a complex being. Let’s now take a look at how your brain communicates with the rest of your body. For this, we will have to turn to your peripheral nervous system (PNS).

(Dr. Kavitha Chinnaiyan)

YOUR AUTOMATIC TRANSMISSION

Your peripheral nervous system has two parts, the somatic and the autonomic ner- vous system (ANS). Your somatic system is under your voluntary control and con- sists of the nerves that connect your sense organs (eyes, ears, nose, skin, mouth) and organs of action (hands, legs, organs of excretion, reproduction, and speech) with your brain. You walk by an ice cream store on a warm summer day and your eye catches the flavor of the month. It is cookie dough, your favorite. You must have some. You walk in and treat yourself to a cone. Here, your eyes took in infor- mation to the neocortex via sensory neurons.

Your limbic system, which has learned from previous experience that cookie dough is good, gave meaning to the information in the neocortex (“Yum, gotta have some!”) and the neocortex regis- tered it, sending impulses down motor neurons to walk in, order, pay, and take a lick of the delicious treat. Ahead, we will see how you first decided that cookie dough was pleasurable.

Your autonomic nervous system lies outside your voluntary control and con- sists of your hypothalamus, brain stem, and spinal cord. Recall that your hypo- thalamus is also part of your reptilian brain. This is because it determines the hor- monal responses that are necessary for optimal body function. The ANS has two arms: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems. One difference between the central nervous system (CNS) and autonomic nervous system (ANS) is that the CNS neurons connect directly to the organs, while those of the ANS have an intermediary neuron. The neuron from the brain connects to the inter- mediary, which then connects to the organ.

Picture this: you are driving along the freeway at seventy miles an hour when your phone beeps, indicating an incoming text. Without slowing down, you take your eyes off the road to read it. When you look up, the traffic has come to an unex- pected stop. In an instant your pupils dilate, blood flow is diverted from the stom- ach and digestive organs to your arms and legs, your salivary glands freeze, and your liver releases its store of glucose. Without conscious thinking, you slam your brakes and come to a stop, narrowly missing the car in front of you. Only then do you realize that your heart is pounding and you’re breathing fast. Meet your sympa- thetic nervous system, the actions of which are mediated by the hormone called norepinephrine. Its job is to spring you into action in what is called the flight- or-fight response. It floods the body and redirects your energy and resources to do what you need to do now.

In the face of danger, the body doesn’t care about digesting your lunch or keep- ing your mouth moist. It needs energy to act, which comes from the spurt of glu- cose. The hands and legs that need to run or stay and fight need more blood, which is redirected from other organs. You need better eyesight: the pupils dilate. Your heart works harder to provide more blood flow to the body, and your breath- ing gets faster to take in more oxygen.

When you are relaxing after a big Sunday brunch with nothing pressing to do, you can get a feel for your parasympathetic nervous system. Its main job is to digest your food and allow your body to rest. The neurotransmitter responsible for the rest-and-digest response is called acetylcholine, which stimulates the digestive organs to work, lowers heart rate and blood pressure, and constricts the pupils and the airways since you don’t need to see particularly well or breathe as hard for this function. Although the ANS functions well in times of stress to ensure your survival, there is a caveat. Chronic stress, as we will see in the next chapter, creates a per- petual loop of distress signals that have a direct impact on the heart.

(Dr. Kavitha Chinnaiyan)

THE I-MAKER

It turns out that only 5 percent of the brain’s total energy consumption is for fo- cused tasks such as reading or working on a project. Most of the brain’s energy is consumed in the ongoing personal narrative that weaves together the various ex- periences of our lives into one coherent story. In other words, the brain uses most of its energy ensuring that you remain the protagonist in the story of your life. For this, you can thank your default mode network (DMN).

The DMN is a network of various brain centers that light up simultaneously when focused attention is not required. Consisting of three arms, it is the network that brain activity defaults to. The first arm is responsible for the personal autobio- graphical storytelling, or the I-making that is self-referencing (thoughts that revolve around why you like or don’t like something and how these choices define you) and validates your own emotional state. Any time you are retelling your story in your mind, this network is active. The second arm of the DMN is associated with assuming what someone else knows or doesn’t know, understanding someone else’s emotional state, moral justification, assessing right and wrong, and evalu- ating the social standing of your family, group, or tribe. The third arm of the DMN is associated with recalling the past, imagining the future, and the ability to con- nect the two into a story.

The DMN keeps the I alive and well. The curious thing about the I is that it con- sists of fragments of information such as your likes and dislikes, your ancestry, and how you feel about your nose, body, job, spouse, children, or race. The I isn’t one thing but a whole box of ideas about who you think you are. You collected these ideas over the course of your life and then built your identity upon them, and you’ve collected them because each came with a distinct emotional high or low that created particular neurohormonal superhighways.

We collect most of the ideas about who we are before the age of seven. The younger we were when an emotional signature arose, the more surely was a super- highway created. This is when we started believing things like “I’m cute,” “My nose is too big,” “I’ll never be good at sports,” or “I’m a good musician.” In adolescence our superhighways were reinforced as we added on to our existing beliefs, strengthened them, and added new ideas based on more complex concepts like religion and politics. Unlike in childhood, stories around our ideas become more complex in adolescence. As young adults we embellish our beliefs with more elab- orate and sophisticated stories. The I is created through the self-referencing part of the DMN, which is cemented by our beliefs and tying them all together. However, even though our nerves fire in certain ways that seem to point to our identity, the I doesn’t live in the brain.

Exercise: Where Are You? Try this exercise right now.

• Close your eyes and take a few deep breaths. Relax fully.

• Contemplate the following: Spatially speaking, where is your sense of I at this moment? Are you in your liver? Colon? Kidneys? It is very easy to understand that of course we are not located in our abdominal organs.

Can you be in the brain then? Think of Einstein’s preserved brain. Is he in his brain? If we dissected your brain, will we find you in there? Think of people that lose limbs in tragic accidents or those that have parts of their brains surgically removed. Do they lose a part of their I?

• If you’re not in your body, where are you? If you said mind, you’d be partially correct, but then where is your mind if it is not within your brain cells?

• The popular way of thinking is that the brain creates your I, but we have seen earlier that the body has no capacity to spin stories. Even though our bodies are supremely intelligent, as we shall see later, they act and react by way of chemical and electrical signals. If we performed a laboratory exper- iment to re-create these signals between nerve and gland cells, would a mind appear? If so, where would it show up?

• If you don’t know where you are, can you know who you are? Sure, your body is sitting (or standing or lying down) as you read this, but who are you really?

Notice that when you refer to your body parts, you use prepositions like “mine” that denote they belong to you. Even in daily language, you are assuming that there is an I that owns the body and the mind. Your day-to-day language gives away the fact that you don’t really think that you are your body or your mind.

Even though we don’t really think we are our body-mind, we continue to identify deeply with it, which causes us to maintain our learned behaviors and fixed ways of thinking and feeling. Patterns of thinking and feeling create specific neuro- hormonal superhighways, ensuring that we continue to think and act in the same habitual ways. Like hamsters on wheels, we get stuck in our body-mind-I loops. If the body suffers, I suffer. If the mind is shaken up, I become discombobulated. The I is essentially based on fear of suffering and desperate wanting to be free of fear and suffering. And because this cannot be guaranteed, the fragile I fights to keep itself alive.

An ancient definition of health includes being saturated with bliss. We cannot be saturated with bliss if our sense of I is being constantly threatened! The path to bliss requires us to question the very basis of our existence, which we will do when we examine the bliss model in detail in the next chapter.

(Dr. Kavitha Chinnaiyan)